There is lot of talk, presently, about exoplanets, or extrasolar planets as they are also called. Since the discovery in 1995 [1] of the first planet orbiting around a star other than the Sun, one realized that the planets of our solar system are not exceptions. Up to now, 900 of them have been discovered, and several thousand candidates are waiting to be confirmed. The first to be detected were mainly giant gaseous ones like Jupiter and Saturn, improper for life, but rapid instrumental progress allowed to discover smaller and rocky planets, which could resemble our good old Earth. These are in fact the most numerous, as shown by their distribution. Note that some planets have been found floating freely in space, while most are orbiting around a star.

There are several methods to detect extrasolar planets ; we shall mention only two of them, using respectively spectroscopy and photometry. The first consists in measuring the shifts of spectral lines to determine the velocity of the star perturbed by the presence of the planet. In the second one observes the slight dimming of the star’s luminosity when the planet is crossing the disc of the star. This is how hundreds of planets have been discovered by the satellites CoRoT [2] of ESA and Kepler from NASA. Both methods favour the detection of planets orbiting close to their star, and/or are rather massive.

The extrasolar planets encyclopaedia, developed by Jean Schneider

Jean Schneider, since forty years a member of the Paris Observatory, presently at LUTH, was one of the first persons (with William Borucki, Principal Investigator of the space mission Kepler) to propose, as soon as in 1988, to detect extrasolar planets by the transit method. He began in 1995 to hold a catalogue of exoplanets mentioning their characteristics, which has become the “Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia” that everyone can consult online (http://exoplanet.eu/). To maintain this database up to date, he is in daily relation with the thousand astronomers involved in the subject. His encyclopaedia has become an inestimable tool, and himself is regarded as a key figure in that community. He has long worked alone on this project, but he benefits now from some assistance by a computing expert.

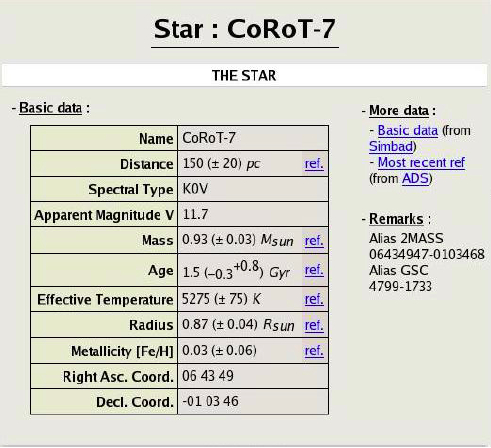

The encyclopaedia is described as it was in February 2011 in an article « Defining and cataloguing exoplanets : the exoplanet.eu database » by Schneider et al. A&A 532, A79, 2011. It evolves continuously. It is organised in 8 tables corresponding to the different methods of planet discovery. For each planet it gives its characteristics as well as those of the host star. In addition, there is an individual page for each planet and each planetary system. More than 10000 references are listed in the bibliography, which contains articles published in scientific journals, preprints, books, conference proceedings and doctorate theses. One can retrieve them by author or by title.

The « exomoons »

A subject has been nagging Jean Schneider for some time, namely the “exomoons”. Indeed, since most planets in the solar system possess one or several satellites, of which some have nearly the size of the Earth, the same must be true for the hundred of million planets residing presumably in the Milky Way. Moreover, these exomoons could be habitable much as the planets around which they are orbiting, and even more so because they are solid whereas their planet is gaseous (like the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn).

Due to their small size, these celestial bodies escape the present observation techniques. But back in 1999 Jean Schneider has shown that they would be detectable through transits using the telescopes of the future, such as the ELT (the extremely large telescope which is planned to begin its operation around 2020). He proposed also to extend the transit method to the “mutual events”, as done for our solar system ; this could allow to reach the size of our own Moon. Anyhow, he expects Kepler to detect an exomoon any time.

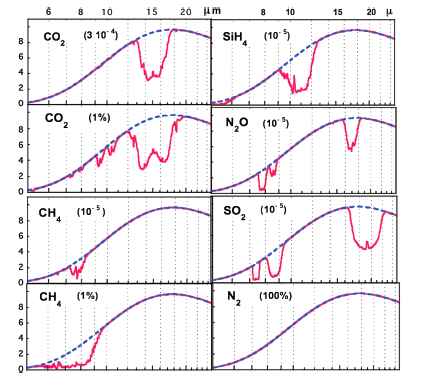

A visionary article published in 2010, « The Far Future of Exoplanet Direct Characterization », which Jean Schneider signed as first author, describes in detail the future steps to characterise directly habitable planets. It concludes that our followers will have to wait a long time before seeing directly the morphology of extrasolar organisms.

We are approaching the thousandth detected exoplanet, but Jean Schneider refuses to celebrate this event, because certain objects presently listed as planets may well turn out to be “brown dwarfs”, e.g. objects that are more massive than planets but less than stars, and bound to be removed from his encyclopaedia after further observations. We believe however that the Paris Observatory should pay tribute to his enormous and meticulous work, and should celebrate this thousandth planet, even without his agreement !

[1] In fact, already in 1992 two planets have been discovered orbiting around a pulsar. Their detection was based on measuring the variation of the period of the pulsar, from which one can deduce the main orbital parameters of the bodies responsible for these perturbations. Furthermore, the object HD 114762 b, discovered in 1989 and initially classified as a brown dwarf, is now considered as a planet.

[2] It was Jean Schneider who suggested using CoRoT, first designed to measure stellar oscillations, to detect extrasolar planets.