In 1922, Mary Lea Heger, then working for a Ph.D. at the Lick Observatory in the USA, highlighted the presence in interstellar spectra of a number of weak absorption lines of unknown origin.

A few years later, astronomers realized that the interstellar medium was responsible for these lines, which were then dubbed DIB, standing for “Diffuse Interstellar Bands”.

During the century which followed this discovery, astronomers discovered over 400 such bands.

Nevertheless, the molecular species which produce these bands are still unknown The most likely candidates are carbonaceous macro-molecules in a free state in the interstellar clouds.

These bands are truly interesting for astronomers, since they could be the signature of a vast reservoir of organic matter in galaxies.

Note however that the signature is extremely weak, and thus hard to find.

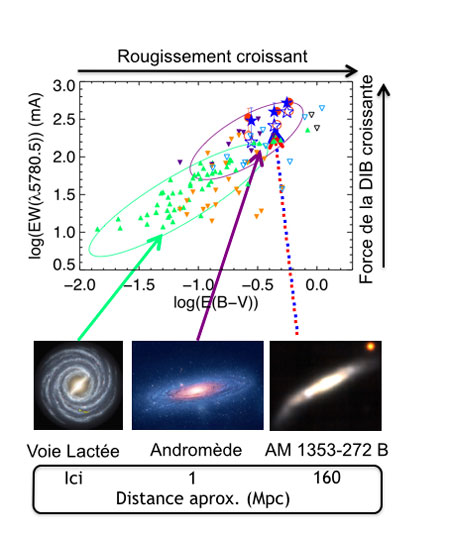

Till now, astronomers have only been able to map in a fragmentary way certain regions within the Milky Way ; as far as the other galaxies of the Local Group are concerned, the signatures have only been found in disparate regions.

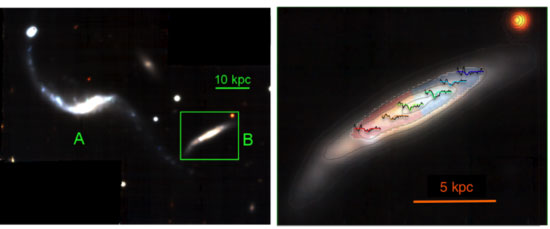

Using data furnished by the new MUSE instrument at the VLT, a team of astronomers led by Ana Monreal-Ibero, from the GEPI, and Peter Weilbacher from the Leibniz-Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam, has managed to identify one of these mysterious bands in a huge part of an interacting galaxy , part of a system nicknamed "the dentist’s chair".

This feat is due to the fact that this galaxy, 160 Mpc away, is more than two orders of magnitude away from the other galaxies for which these bands had already been observed.

The DIBs detected are indicated above the galaxy. Note how weak they are. That they could be seen is due to the use of an extremely sensitive spectrograph with a large aperture telescope, and the fact that other stronger spectral lines of the interstellar medium were observed.

With this discovery, the team has shown that it is now possible to map these signatures in distant galaxies.

Using very sensitive instruments with large telescopes, astronomers hope to be able one day to answer the following question : at which point during the evolution of galaxies, and under what conditions, emerged the still mysterious organic species at the root of the DIBs ?