<<

Astrometrists quickly found its origin : it was a comet orbiting Jupiter which was broken up during its previous passage near the planet, in July 1992 ; according to forecasts, the fragments will be caught by the planet’s gravity field the next time it passes close to Jupiter. We can therefore expect a series of successive impacts which will occur between July 16 and 22, 1994. The impacts will take place on the 44th parallel of the southern hemisphere, and, given the speed of rotation of the planet on itself, will be distributed at various longitudes.

Planetary mobilization

From that moment on, astronomers were mobilized. Such an event is not commonplace ; they see it as an opportunity to observe in real time - and without danger ! - the consequences of a major meteorite impact in a planetary atmosphere.

Observations are being prepared, using cameras and spectrometers in all wavelength ranges, from ultraviolet to radio waves. Space resources were also called upon, starting with the Hubble telescope and the Galileo probe, then cruising towards Jupiter. These space observations from Galileo were invaluable, as their angle of view was different from that from Earth, enabling them to observe the first phases of the phenomenon, whereas observations from Earth would only begin a quarter of an hour after the impact, as it occurred beyond the visible edge of the planet.

A great deal of uncertainty reigns in observatories on the eve of the first impact. Will it be detectable ?

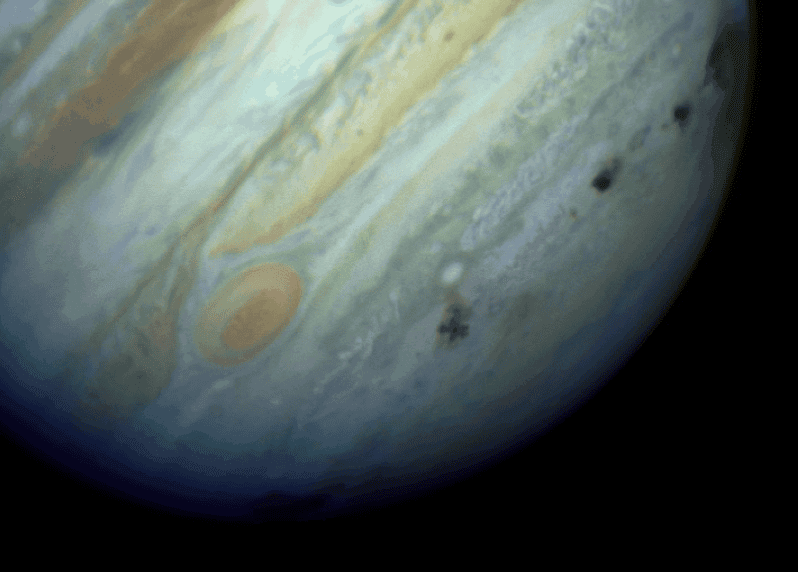

The answer is yes. The fall of the first impact produces a fireball whose temperature exceeds 20,000 degrees, and matter is ejected up to an altitude of 3,000 km, as observed by images from the Hubble telescope.

Fifteen minutes later, the falling debris formed a large patch around the impact site, which would remain visible for weeks.

New molecules are formed at high pressure and temperature (H2O, HCN, CO, OCS...), some of which will persist for months or even years.

The same scenario will be repeated for subsequent fragments, with more or less amplitude depending on the size of each object.

Lucky to have lived through this great moment

At Paris Observatory, many of us were involved, particularly in the infrared and millimetre spectroscopy measurements. From all the data, we were able to establish that comet Shoemaker-Levy 9, before being fractured, was about 1 km in diameter.

An event such as the fall of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 on Jupiter is very rare on a human timescale, but far from unique in the history of the Solar System. On July 19, 2009, a smaller bolide collided with Jupiter and left a few traces on the planet ; it was probably an asteroid. Other similar phenomena, of lesser amplitude, were subsequently observed. They are regularly monitored by groups of amateur and professional astronomers.

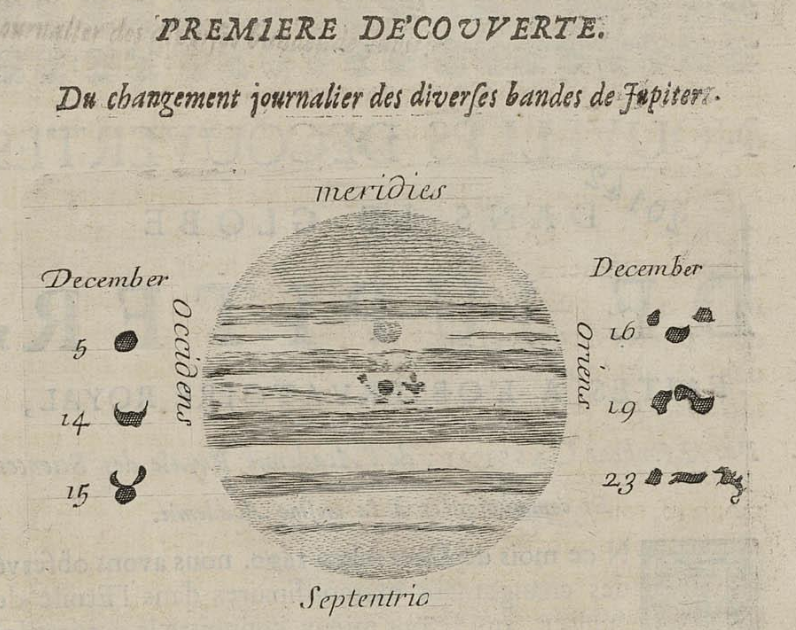

The first director of the Paris Observatory, Jean-Dominique Cassini (1625-1712), wrote in Le Journal des Sçavans about new spots that appeared on the disk of Jupiter in December 1690 ; he had been able to follow the evolution of these structures for over two months.

Beyond the appeal of the powerful cosmic forces at play, witnessing this type of phenomenon is always a rich source of information on the importance of collisions in the history of the Solar System. >>