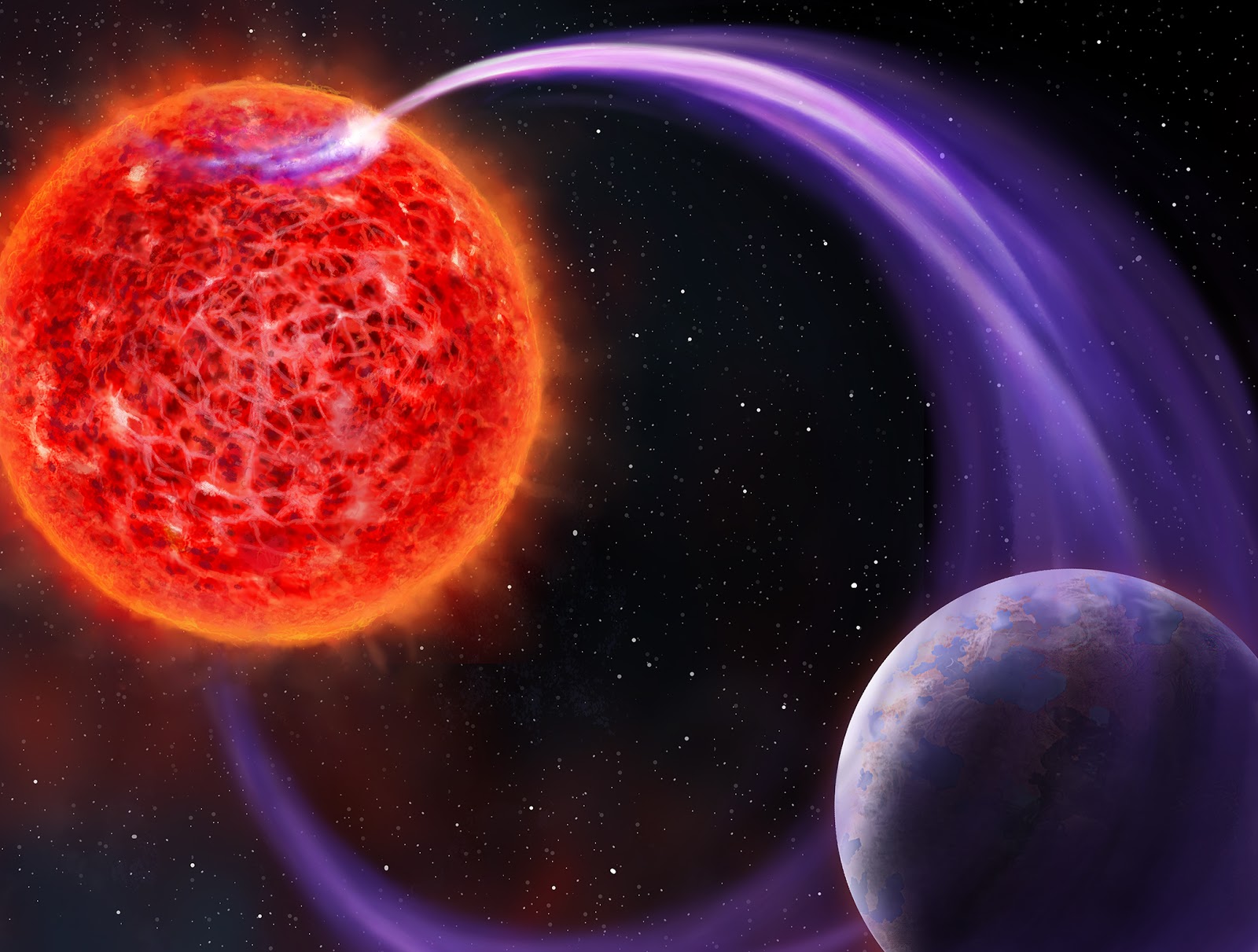

Red dwarfs are the most abundant type of star in our Milky Way, but much smaller and cooler than our own Sun. This means for a planet to be habitable, it has to be significantly closer to its star than the Earth is to the Sun. Red dwarfs also have much stronger magnetic fields than the Sun, which means, a habitable planet around a red dwarf is exposed to intense magnetic activity. This can heat the planet and even erode its atmosphere. The radio emissions associated with this process are one of the few tools available to gauge the potency of this effect.

"The motion of the planet through a red dwarf’s strong magnetic field acts like an electric engine much in the same way a bicycle dynamo works. This generates a huge current that powers aurorae and radio emission on the star." says Dr Harish Vedantham, the lead author of the study and a Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) staff scientist.

Thanks to the Sun’s weak magnetic field and the larger distance to the planets, similar currents are not generated in the solar system. However, the interaction of Jupiter’s moon Io with Jupiter’s magnetic field generates a similarly bright radio emission, even outshining the Sun at sufficiently low frequencies.

"We adapted the knowledge from decades of radio observations of Jupiter to the case of this star" said Dr Joe Callingham, ASTRON postdoctoral fellow and co-author of the study. “A scaled up version of Jupiter-Io has long been predicted to exist in the form of a star-planet system, and the emission we observed fits the theory very well.”

The group is now concentrating on finding similar emission from other stars. “We now know that nearly every red-dwarf hosts terrestrial planets, so there must be other stars showing similar emission. We want to know how this impacts our search for another Earth around another star” says Dr Callingham.

The team is using images from the ongoing survey of the northern sky called the LOFAR Two Metre Sky Survey (LoTSS) of which Dr Tim Shimwell, ASTRON staff scientist and a co-author of the study, is the principal scientist. “With LOFAR’s sensitivity, we expect to find around 100 of such systems in the solar neighborhood. LOFAR will be the best game in town for such science until the Square Kilometre Array comes online.” says Dr Shimwell.

The group expects this new method of detecting exoplanets will open up a new way of understanding the environment of exoplanets. “The long-term aim is to determine what impact the star’s magnetic activity has on an exoplanet’s habitability, and radio emissions are a big piece of that puzzle.” said Dr Vedantham. “Our work has shown that this is viable with the new generation of radio telescopes, and put us on an exciting path.”

Paper link

« Coherent radio emission from a quiescent red dwarf indicative of star–planet interaction » is published in Nature Astronomy on 17 February 2020 :

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-020-1011-9

To know more about LOFAR

The international LOFAR telescope (ILT) consists of a European network of radio antennas, connected by a high-speed fibre optic network spanning seven countries. LOFAR was designed, built and is now operated by ASTRON (Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy), with its core located in Exloo in the Netherlands. LOFAR works by combining the signals from more than 100,000 individual antenna dipoles, using powerful computers to process the radio signals as if it formed a ‘dish’ of 1900 kilometres diameter. LOFAR is unparalleled given its sensitivity and ability to image at high resolution (i.e. its ability to make highly detailed images), such that the LOFAR data archive is the largest astronomical data collection in the world and is hosted at SURFsara (The Netherlands), Forschungszentrum Juelich (Germany) and the Poznan Super Computing Center (Poland). LOFAR is a pathfinder of the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), which will be the largest and most sensitive radio telescope in the world.