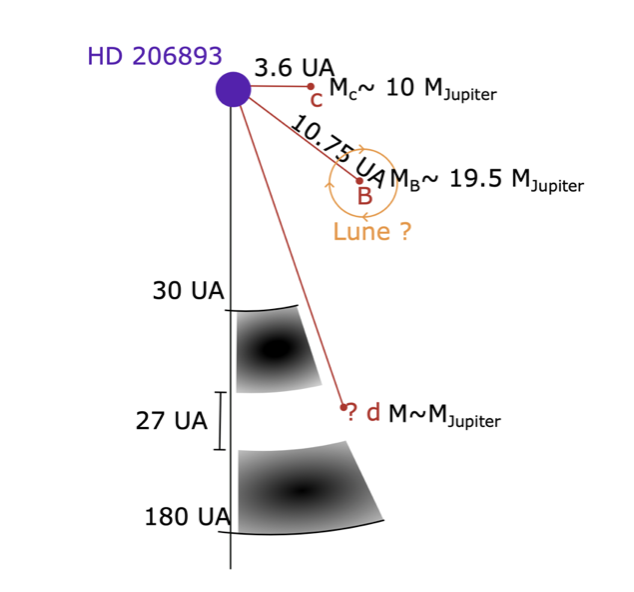

Exomoons, moons orbiting planets or substellar companions outside the Solar System, are among the most difficult objects to detect in astronomy. In a new study led by Quentin Kral, a researcher at the Paris Observatory-PSL, a particularly intriguing astrometric signal has been detected around HD 206893 B, a massive companion with a mass of about 20 Jupiters orbiting a star located about 40 parsecs from Earth.

![<multi>[fr] Vue d'artiste du système HD 206893 : un compagnon substellaire orbite autour de l'étoile, et pourrait lui-même héberger une exolune massive. [en]Artist's impression of the HD 206893 system: a substellar companion orbits the star and could itself host a massive exomoon.</multi>](IMG/png/hd_206893.png)

The study is based on observations obtained with GRAVITY, an interferometric instrument installed on ESO’s Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI) in Chile, which combines the light from the four 8-meter telescopes of the VLT. GRAVITY achieves exceptional astrometric precision, which is essential for probing the most subtle movements of extrasolar systems.

Unlike traditional astrometric approaches, which are generally based on observations spaced several years apart, this study uses intensive monitoring over short time scales, ranging from a few days to a few months. This strategy makes it possible to probe rapid dynamic variations that have not been explored until now.

A periodic motion consistent with an exomoon

The data show that HD 206893 B does not follow a regular orbit around its star. Superimposed on this main motion, a slight periodic back-and-forth motion is detected, with a period of about nine months and an amplitude comparable to the Earth-Moon distance.

“This type of signal corresponds exactly to the gravitational effect expected if the object is disturbed by an orbiting companion, such as a massive exomoon,” explains Quentin Kral, PI of the study.

Various alternative scenarios were explored to explain the observed signal, including effects related to the companion’s own orbit or instrumental uncertainties. The analysis shows that models including an exomoon provide a significantly better fit to the available data.

A candidate with extreme properties

If the interpretation in terms of an exomoon is correct, the object would be exceptionally massive, with an estimated mass of about half that of Jupiter, or nearly nine times the mass of Neptune. It would orbit HD 206893 B at a distance of about 0.22 astronomical units, in an orbit that is highly inclined—about 60 degrees—to the orbital plane of the companion around its host star.

Such properties would place this object in a still unexplored regime, on the borderline between a giant exomoon and a very low-mass companion, illustrating the current vagueness of definitions in this field.

A cautious but promising detection

However, the authors stress that it is premature to speak of a definitive detection.

“For objects as difficult to detect as exomoons, the level of confidence required is extremely high,” says Sylvestre Lacour, who participated in the study. “At this stage, it is a particularly strong candidate, but confirmation will require additional observations,” says Mathias Nowak, another author.

Requests for additional observation time have been submitted to verify whether the signal repeats consistently, as expected for an orbiting companion.

A new approach to searching for exomoons

Until now, most searches for exomoons have relied on the transit method, which is mainly sensitive to planets very close to their star. The approach developed here, based on high-precision interferometric astrometry, targets massive companions in wide orbits, environments where exomoons are theoretically more stable.

This study demonstrates that high-precision astrometry can detect the dynamic signal induced by a massive exomoon and proposes a clear observational strategy for extending this research to other promising systems identified in the article.

Bibliography

Kral et al.

Astronomy & Astrophysics, accepté pour publication

arXiv:2511.20091

https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202557127